Perhaps no other passage in the first chapter of Genesis has generated more analysis and debate than v. 26, not only amongst bible scholars, but also with theologians as well. Here is the verse:

Then God said: Let us make human beings in our image, after our likeness. Let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, the birds of the air, the tame animals, all the wild animals, and all the creatures that crawl on the earth. (NABRE)The two big questions this passage raises are: 1) Why is God speaking in the first-person plural? And 2) What is meant by the “image and likeness” of God? I had intended to address these questions in just one blog article, but that response got so long that I needed to break it up into two separate articles. Therefore, in the rest of this article, I will deal with the first question on the use of the divine plural. In my next article, I will complete the discussion on the “image of God”.

“Let us make human beings in our image…” Who is God talking to here? The divine plural is used only here, in Gen 3:22 and 11:7, and in Isaiah 6:8. The passage from Isaiah is particularly instructive. The prophet describes a vision of the Lord, seated on his throne, with seraphim stationed above him. There are other examples in the OT of God presiding over an assembly of heavenly beings (1 Kings 22:19-22; Psalms 82; Job 1:6; 2:1). When Isaiah hears the voice of the Lord saying, “Whom shall I send? Who will go for us?” it is understood that God is addressing the heavenly court.

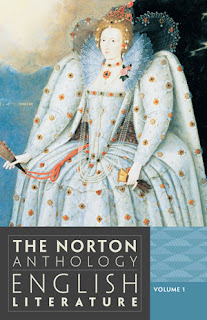

|

| God surrounded by the host of heaven in Michelangelo's "Creation of Adam" on the Sistine Chapel. |

This is perhaps the most common explanation for the use of the divine plural here and in the other passages in Genesis, but there are some problems with this explanation. Unlike Isaiah, a heavenly court has not been described in Genesis. If the reader were to assume such a heavenly assembly, those being addressed are not merely being consulted, but are also included in the act of creation (“let us make…in our image”). Finally, the following verse (1:27) states that this image is, in fact, the “image of God”. So if this explanation of God addressing a heavenly court were correct, the author would be saying that the assembly of divine beings are part of God. Since the author of Genesis 1 goes to great pains to assert that God is unique and acting alone in the creation, this seems unlikely.

Since the early days of the Christian Church, this passage has been interpreted as referring to the Trinity. God the Father is addressing either the Son or the Spirit, or both. Gen 1:2 could be translated as saying either “a mighty wind” or “the spirit of God” was hovering over the abyss. Some commentators, latching on to the “spirit of God” translation, claim this as evidence of at least a duality within the Godhead: the creator and the spirit. But there are problems here as well. The idea of the Trinity is unknown in the OT and there is nothing to suggest the divine plurality in the verse is limited to three persons. In v. 29, the author is back to using first-person singular (“I give you every seed-bearing plant…”), so the divine plural is not used for direct dialogue. (This would also eliminate the possibility that the divine plural is similar to the royal “we” used by a king or queen. Also, there are no examples of the royal plural in the OT.)

Since we only see the divine plural used (in Gen 1:26, 3:22, and 11:7) where God is addressing himself and not in other instances (such as Gen 1:29) when God is addressing human beings, perhaps the best explanation for the use of the divine plural is one of self-deliberation or self-decision, much as we might say to ourselves, “Let’s see” or “Let’s do this.” A parallel for similar usage would be Song of Songs 1:9-11 where the lover speaks in the first-person, using the same words of Gen 1:26: “Let us make ornaments of gold studded with silver.”

If this interpretation is correct, then there’s no great theological point being made with the choice of words. It is simply a rhetorical device on the part of the author. One may, of course, choose to believe that the divinely-inspired author is – maybe subconsciously – revealing the germ of a Trinitarian understanding of God that can only be fully understood in retrospect, in light of later church doctrine. Such an interpretation is not impossible, but it hardly seems to be the intention of the human author.

With that out of the way, we’ll look at what the “image and likeness” of God means in my next article.