Hannah and the Presentation of Samuel

To understand the background of Luke’s scene of the presentation of Jesus in the Temple, we have to return again to the story of Hannah in the OT (1 Samuel 1:1-2:11). As we have seen previously, Hannah was the favored, but childless, wife of Elkanah. On a visit to YHWH’s sanctuary at Shiloh, Hannah promised that if she were to bear a male child, she would dedicate him to God as a nazirite. Seeing Hannah praying in the sanctuary, the aged priest Eli assured her that her prayer would be answered. After Samuel was weaned, Hannah took him to the sanctuary and presented him to Eli, and Samuel remained in service to YHWH.

Luke presents a version of that OT scene, but confuses two different customs: the purification of the mother and the presentation of the firstborn male child. Leviticus (12:1-10) specifies that, following birth, a woman is ritually unclean for forty days, after which time she shall present at the sanctuary the offering of two young pigeons or doves (see Lk 2:24). Exodus (13:11-15) demands the consecration of all firstborn sons, but Numbers (18:15-16) allows the firstborn to be redeemed from service to YHWH for five shekels. Bringing the child to the sanctuary is not a requirement.

Just as Luke employed the census to bring Joseph and Mary from Nazareth to Bethlehem, he now utilizes the purification ceremony to bring the couple to Jerusalem. This allows him to end the infancy narrative in the Jerusalem Temple, just as he began the infancy narrative in the Temple with Gabriel’s annunciation to Zechariah. Since Jesus is being redeemed and not dedicated, there is no need to present him in the Temple, but Luke wants to parallel the story of Hannah presenting Samuel to Eli, with the aged Simeon standing in for the priest Eli.

Simeon and the Oracle of the Pierced Soul

Simeon is described in OT terms: “upright and devout and waiting for the consolation of Israel.” He is also described as something of a prophet, so Luke is joining the themes of Law (purification of the mother, presentation of the firstborn) and the Prophets. Simeon takes the child Jesus in his arms and utters two prophetic oracles. We have previously discussed the first oracle (Lk 2:29-32), the Nunc Dimittis, as well as the second oracle (Lk 2:34-35) foretelling that Jesus will bring about division.

|

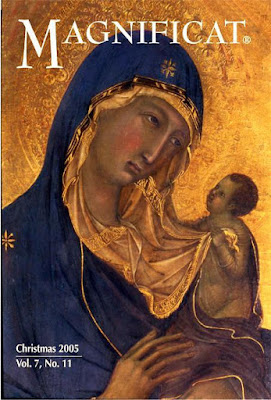

| In Catholic iconography, the Virgin Mary is frequently portrayed with a sword through her heart. This represents Simeon's prophecy in Luke 2:35 that a sword will pierce her soul. |

First, some background on the imagery. The closest OT parallel is Ezekiel 14:17 wherein the sword is one of the judgments – the others being famine, wild beasts, and plague – God will send to punish the land; some will die but others will live. So it is not just a punishment, but a discriminating judgment. What Luke seems to be trying to say is that the sword of division will also affect Mary; she must choose if she will accept or reject Jesus.

There is one scene in the public ministry where Mary appears in all three synoptic gospels. This is the scene where Mary and the brothers of Jesus come to him. In the Marcan form of this (Mk 3:31-35), his family comes out of concern that Jesus is “out of his mind” (Mk 3:21). Because his family fails to understand his mission, Jesus rejects his family. He asks rhetorically, “Who are my mother and my brothers?” before looking at the crowd around him, saying, “Here are my mother and my brothers.” In the Lucan version (8:19-21), the rhetorical question and gesturing to the crowd are eliminated, leaving only Jesus’ proclamation, “My mother and my brothers are those who hear the word of God and do it.” In Luke’s gospel, Mary and his brothers are part of Jesus’ family not merely because of a biological connection, but because of their response to the gospel.

Unlike Mark who has a negative view of the immediate family of Jesus, Luke sees them as model believers and shows them as part of the early Church awaiting the spirit on Pentecost (Acts 1:14).

Anna and the Return to Nazareth

The elderly prophetess Anna is mentioned only briefly. Perhaps Luke wanted both her and Simeon in the Temple at the end of his story to balance the aged Zechariah and Elizabeth at the beginning of his story. Or, perhaps he didn’t want to end the infancy narrative on the foreboding note of Simeon’s second oracle.

For someone so briefly mentioned that not even her dialogue is quoted, Luke provides curious detail in her biographical note, providing the name of her father and her tribe. V. 37 either describes her as having been a widow for 84 years, or states that she is a widow of 84 years of age. If the former, she would have to be around 103 years old. While that sounds ridiculous, it would be reminiscent of the heroine Judith, a widow who lived to be 105 (Judith 16:22-23). Widows seemed to have a special role in the early church (1 Tim 5:3-10).

Vv. 39-40 bring the infancy narrative to a close as Joseph and Mary return to Nazareth, the child growing up, filled with wisdom and favored by God. These last lines recall the ending of the story of Samuel (1 Sam 2:20-21) in which Elkanah and Hannah returned to their home after presenting Samuel to Eli and the boy Samuel grew in the presence of YHWH. Luke is preparing the reader for the appearance of the adult Jesus of Nazareth, preaching a message of wisdom and exemplifying God’s favor.