- Morning: the “Canticle of Zachary” (Lk 1:68-79), commonly called the “Benedictus”

- Evening: the “Canticle of Mary” (Lk 1:46-55), commonly called the “Magnificat”

- Night: the “Canticle of Simeon” (Lk 2:29-32), common called the “Nunc Dimittis”

Luke inserted these canticles into an existing pre-Lucan narrative. If you remove them, the narrative flow is not interrupted (for example, Lk 1:80 follows smoothly after 1:66) and you would not know they were missing. Luke did not invent them, however. The style is slightly different in each and, except for a verse or two that Luke probably added, the canticle has nothing to do with the character reciting it or the immediate situation. It’s like watching a Broadway play when a character suddenly breaks into song and then, after the song, everything goes back to normal.

Some scholars believe that Luke’s canticles were originally prayers created by early Jewish Christians, based on verses from the OT. They certainly fit a Jewish hymnic style found in documents dating from 200 BC to 100 CE. If this theory is correct, then these are perhaps the oldest preserved Christian prayers of praise. It is highly appropriate, therefore, that Luke places them on the lips of the first Jewish believers in the good news of salvation realized in the births of John the Baptist and Jesus.

The Benedictus (Lk 1:68-79)

This canticle is spoken by Zechariah, the father of John the Baptist, after the naming of the child. It takes its name from its first words in Latin (Benedictus Dominus Deus Israel, “Blessed be the Lord God of Israel”). In the classification of hymns that is applied to the Psalms, it would best fit the category of a hymn of praise to the God of Israel.

Although the hymn is proclaimed in thanksgiving for the birth of John, it contains mostly messianic references. It is likely that Luke inserted vv. 76-77 to fit the canticle into the context of the birth of John the Baptist:

Some scholars believe that Luke’s canticles were originally prayers created by early Jewish Christians, based on verses from the OT. They certainly fit a Jewish hymnic style found in documents dating from 200 BC to 100 CE. If this theory is correct, then these are perhaps the oldest preserved Christian prayers of praise. It is highly appropriate, therefore, that Luke places them on the lips of the first Jewish believers in the good news of salvation realized in the births of John the Baptist and Jesus.

The Benedictus (Lk 1:68-79)

This canticle is spoken by Zechariah, the father of John the Baptist, after the naming of the child. It takes its name from its first words in Latin (Benedictus Dominus Deus Israel, “Blessed be the Lord God of Israel”). In the classification of hymns that is applied to the Psalms, it would best fit the category of a hymn of praise to the God of Israel.

Although the hymn is proclaimed in thanksgiving for the birth of John, it contains mostly messianic references. It is likely that Luke inserted vv. 76-77 to fit the canticle into the context of the birth of John the Baptist:

And you, child, will be called the prophet of the Most High;In the inserted lines above, it is clear that John is merely the one who goes before the Lord to prepare the way. In the lines prior to this Lucan insertion, the canticle speaks of fulfilling the promises made to David (vv. 68-71) and remembering the oath sworn to Abraham (vv. 72-75). Matthew also wanted to stress that Jesus was a Son of David and a Son of Abraham. These completed actions of salvation are described in the past tense, even though in the context of the narrative, Jesus has not yet been born.

for you will go before the Lord to prepare his ways,

to give knowledge of salvation to his people

in the forgiveness of their sins.

|

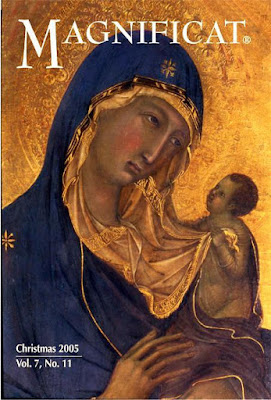

The cover of this issue of the Catholic magazine Magnificat is a detail of the Madonna and Child (c. 1315) by Duccio di Buoninsegna

|

The Magnificat (Lk 1:46-55)

The Magnificat (Latin for “[my soul] magnifies”) is a canticle spoken by Mary after being praised by Elizabeth, her kinswoman. The opening verse parallels the opening verse of Hannah’s canticle (1 Sam 2:1-2) after the birth of Samuel. Compare:

“My heart is strengthened in the Lord, my horn is exalted in my God…I have rejoiced in thy salvation.” (1 Sam 2:1, LXX)

“My soul magnifies the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior.” (Lk 1:46-47, RSV)The Hannah parallelism continues in the next verse, which is probably a Lucan insertion to the hymn to fit its current context; “Because he has regarded the low estate of his handmaid” echoes 1 Sam 1:11: “O Lord of Hosts, if you will look on the low estate of your handmaid.” In responding to the angel Gabriel a few verses earlier (Lk 1:38), Mary referred to herself as “the handmaid of the Lord.” The word translated handmaid is literally the feminine form of the Greek word for “slave.” Not just poetically beautiful, the word reflects the socioeconomic situation of the first Christians who were predominately found among the slave class.

This theme continues in vv. 51-53 which speaks of casting down the mighty and exalting those of low degree. These verses mirror Hannah’s hymn in 1 Sam 2:7-8 which also speaks of raising up the poor to seat them with the mighty. But more than just recapitulating verses from the OT, the Magnificat also foreshadows the gospel message of the Sermon on the Plain (Luke’s version of Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount) in Lk 6:20-26: “He has filled the hungry with good things, and the rich he has sent away empty.”

Whereas Zechariah praised God for sending the messiah who would fulfill the hopes of Israel, Mary interprets what the sending of the messiah means in concrete terms: strength, exalting the lowly, feeding the hungry.

The Nunc Dimittis (Lk 2:29-32)

When Joseph and Mary presented Jesus in the Temple, an old man named Simeon blessed God in an oracle known as the Nunc Dimittis (from the Latin for “Now you dismiss…”). He also blessed the couple with a second oracle concerning the sign to be contradicted.

The themes and phrasings in the Nunc Dimittis are very reminiscent of various passages from the latter half of Isaiah: seeing salvation (52:9-10), the sight of all the peoples (40:5), a light to the Gentiles (42:6; 49:6), and the glory for Israel (46:13). Having shown believers drawn from observant Jews (Zechariah, Elizabeth, the shepherds, Simeon) thus far in his gospel, Luke now introduces the Gentiles in this passage. The consolation of Israel will be a revelation for the Gentiles.

In Simeon’s second oracle (Lk 2:34-35), he foretells that Jesus will bring about “the fall and rise of many in Israel,” as well as being “a sign to be contradicted,” so that the “inmost thoughts” may be revealed. And in the NT, “inmost thoughts” always has a negative connotation. From Luke’s vantage point, it was clear that many in Israel rejected Jesus and that the future of the good news lies with the Gentiles. It is why he ends Acts of the Apostles with Paul arriving in Rome, his last recorded words stating: “this salvation of God has been sent to the Gentiles; they will listen” (Acts 28:28).

During the season of Advent, the Church relives the stories of Israel and its expectations of a messiah. It is most appropriate, therefore, to reflect on these ancient Jewish Christian hymns redolent with the language of Israel in its praise of God and promises of deliverance.

No comments:

Post a Comment