That progression from a lived experience to oral history and finally to written history describes how the individual books of the Bible came to be written. Taking the gospels as an example, we begin with the lived experience of people encountering Jesus of Nazareth, particularly those who became his followers. After his crucifixion, they began preaching and telling others about him and his message. As the generation of those who knew Jesus in the flesh began to die off, it became necessary to record those events in writing.

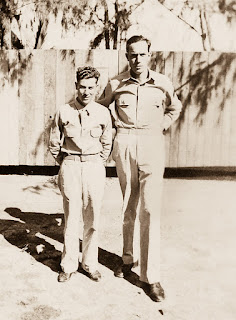

But there’s no guarantee that two people experiencing the same event will remember it in the same way. During his days in the Army, my dad’s best friend was a man named Jacques. Decades after the war, Jacques looked up Dad and they had a reunion. Jacques recalls taking refuge from the bombing with Dad and Dad was certain that Jacques was not with him when he was hiding under the truck. Who was right?

|

| Dad (on left) and Jacques during WWII |

Similarly with the stories of the Old Testament, although it must be said that the further back you go, the longer the period of time between a faith event and its subsequent written narrative becomes. Just because Genesis is the first book of the Bible and describes the creation of the world does not mean that it was the first book to be written down. Genesis has some old traditions in it, but in its current form, it was finalized around the time of the Babylonian Captivity. And that was centuries after the time of the patriarchs.

The thinking used to be that there was a kernel of historical truth in the stories of Israel’s formation (Genesis, Exodus, Joshua, etc.) but archaeological discoveries over the past 50 years have not only failed to find evidence to support that, but have actually found evidence in the opposite direction. Instead of being a pastoral group who escaped slavery in Egypt and infiltrated a Canaanite civilization, it seems that the people of Israel were Canaanite all along. They overthrew the ruling class and invented a foundation narrative centering around a God to whom they gave credit for their origins.

Indeed, there were probably multiple origin narratives and, at some point, these were edited together to form the first books of the Bible that we have today. A classic example of that are the first two chapters of Genesis. In the first chapter, God (Elohim in Hebrew) creates the world in six days with human beings being the last to be created, yet in the second chapter the Lord God (Yahweh Elohim) creates man first, and then the animals, and finally woman. Different names for God are one clue for identifying the varying source material forming the biblical work.

This editorial process went on for many centuries. A third-century BCE Greek translation of the Old Testament (called the Septuagint) shows a number of significant differences from the Hebrew text we have today, shorter in some places and longer in others. This is evidence that the source material was still being shaped by editors.

The takeaway from this is that the Bible did not come about because God whispered into the ears of Moses and others, who then dutifully wrote down the words to form the texts we have today. Neither did inspired authors record historical events as it happened or shortly after the fact. Instead, it is a more complicated process of oral transmission, theological reflection and editing. If we want to refer to the Bible as “the Word of God”, we also have to recognize that it comes to us in human words, subject to the foibles and limitations of human minds.

No comments:

Post a Comment