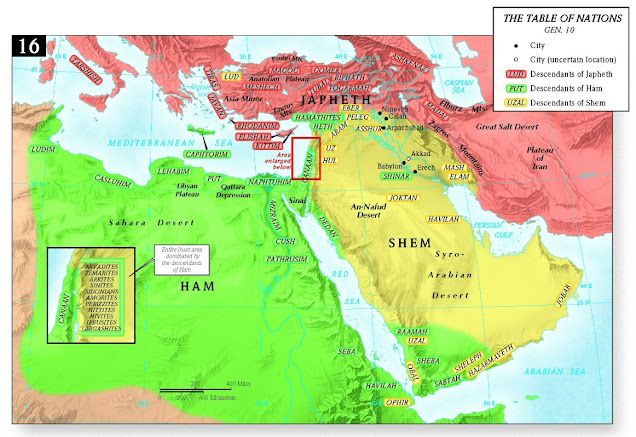

While scholars cannot identify every single name mentioned in Gen 10, they have been able to identify enough to get a rough idea of the lay of the land. As you can see in the accompanying map, the descendants of Japheth are the peoples to the north of Israel in Europe and Asia Minor. Ham’s descendants populate the northern-most parts of Africa and the area immediately surrounding the land of Canaan. The peoples descending from Shem occupy the lands of Mesopotamia and Arabia. These far-flung areas encompassed the known world in Solomon’s day (10th century BCE) but, for the modern reader, fail to take into account the Indian subcontinent, China and other Far Eastern nations, and the indigenous peoples of Australia and the Americas. The great flood is dated by biblical literalists to 2350 BCE, so all of these migrations and racial diversity would have had to take place since that time.

|

| A rough approximation of where the various peoples mentioned in Gen 11 would have been located in the ancient world. |

The literary genre may be that of a genealogy, but the names are not really individuals; they are the names of tribes and regions. In some instances, the writer doesn’t even pretend to provide the name of an individual. In v. 15, J states that Canaan is the father of Sidon (one of the ancient cities of Phoenicia) and Heth (representing the Hittites), as well as the father of several Canaanite tribes (Jebusites, Amorites, Girgashites, and Hivites). And, as if that wasn’t enough, Canaan was also the ancestor of the inhabitants of five Phoenician cities (Arkites, Sinites, etc.).

As mentioned above, there is some duplication of names due to different traditions in the two sources. According to P Lud (assumed to be a reference to inhabitants of Lydia in Asia Minor) are descended from Shem (v. 22), but according to J the Ludites are descended from Ham (v. 13). According to P Havilah and Sheba are descended from Ham (v 7), but J has them descended from Shem (vv. 28-29). It’s all quite confusing.

|

| Presented graphically, the mind-numbing list of names is a little easier to digest. |

The backbone of the Table of Nations is provided by P. He lists the sons of Noah in reverse order, from youngest to oldest. P announces the sons of Japheth, Ham or Shem and then selectively names some grandsons. The passage citing the sons of Japheth (10:2-5) is pure P. P ends each genealogical list with a formulaic conclusion: “These are the descendants of Japheth/Ham/Seth in their lands, with their own language, by their families, in their nations.” A similar formula concludes the chapter.

The list of Ham’s sons (vv. 6-20) is longer because it includes a lengthy addition (vv. 8-19) from the J source. This insertion breaks the monotony by providing us with a few lines (vv. 8-12) describing Nimrod, a mighty warrior and hunter and also the founder of the kingdom of Babel in Shinar (Babylonia) which expanded into Assyria and led to the building of Nineveh. Scholars are not in agreement as to whether the figure of Nimrod can be identified with either a mythological god or hero (like Gilgamesh) or some historical figure. Perhaps he just stands as the representative of the Babylonian nation. It is a bit odd, though, that Nimrod is included in the Hamite list but is said to have established a kingdom in Babylonia which is a Sethite region.

Two brief verses (13-14) relate the origins of the Philistines and the rest of the first J insertion (vv. 15-19) lists various tribes in the land of Canaan and its vicinity. While the division of peoples and nations appears to be along ethnic lines, there are curiosities. The Philistines were of Aegean origins, so they should be listed with Japheth’s descendants, not Ham’s. And the Canaanites were ethnically Semitic, so by all rights they should be counted among the descendants of Shem. Scholars believe that because the Canaanites were under the political control Egypt, the P source listed them as sons of Ham.

Shem is introduced at the ancestor of Eber (v. 21), who we will later see in Gen 11 is the ancestor of Abraham. Without the link to Eber provided by J, we would not know from reading P’s genealogy where to place Israel among Noah’s sons. In a J insertion (v. 26) we further learn that Eber is the father of Peleg during whose lifetime “the earth was divided” (Hebrew palag). This would have been about a hundred years after the flood event and seems to be a reference to the confusion of languages and scattering of peoples across the earth in the following episode of the Tower of Babel (11:1-9). That the descendants of Shem are to be found in Mesopotamia is consistent with the Bible’s claim that Abraham’s home town is Haran (or Ur, depending on the source).

The purpose of the Table of Nations seems to be rather straightforward. The biblical authors are demonstrating that all the known tribes, nations and ethnicities derive from the family of Noah. Therefore, all people are part of an extended family. But the rest of the OT stands diametrically opposed to this notion. Canaanites are not considered “cousins” of Israel, but abominations that needed to be driven out of the Promised Land or exterminated. Perhaps the writer is recalling an older tradition that acknowledged the ties between Canaanite and Israelite civilizations. In fact, archeologists cannot distinguish between Canaanite and Israelite culture; the two blend seamlessly from one into the other.

Either that or the writer is speaking to his audience, an audience that is returning from exile in Babylon to the Promised Land, much as Abraham made that journey. When Abraham arrived in Canaan, he peacefully co-existed with the tribes there. The returning exiles would also arrive to find the land occupied by descendants of the Canaanites. Perhaps the writer wanted to remind his audience that they, too, could peacefully co-exist with the inhabitants if they remembered that they are all descendants of Noah.

No comments:

Post a Comment