- Gen 2:4 These are the generations of the heavens and the earth when they were created.

- Gen. 5:1 This is the list of the descendants of Adam. (the period from Adam to Noah)

- Gen. 6:9 These are the descendants of Noah. (introduces the flood story)

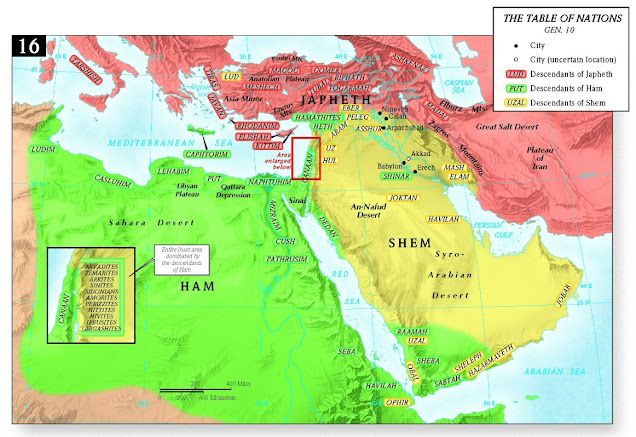

- Gen. 10:1 These are the descendants of Noah’s sons, Shem, Ham, and Japheth... (the Table of Nations)

- Gen. 11:10 These are the descendants of Shem. (the period from Noah to Abraham)

- Gen. 11:27 Now these are the descendants of Terah. (introduces the Abraham cycle)

- Gen. 25:12 These are the descendants of Ishmael… (links Abraham to Arab tribes)

- Gen. 25:19 These are the descendants of Isaac, Abraham’s son… (introduces the Jacob cycle)

- Gen. 36:1 These are the descendants of Esau… (links Jacob to the Edomites)

- Gen. 37:2 This is the story of the family of Jacob. (introduces the Joseph story)

|

Toledot written in Hebrew. Above

it is the name of the first book in the Torah, Bereshit ("In the Beginning"). We call it Genesis.

|

The formula also serves as a cue to the reader. Modern books have chapter and section headings to organize the material, but the biblical books made use of repeated phrases to inform their audience that one section was ending and another section beginning.

The first use of toledot at 2:4 is an especially odd one in that, instead of referring to the descendants of a person, it is referring to the “generations” or “begettings” of the heavens and the earth. It is also unusual in that it serves as a hinge, closing out the P creation account and opening the Yahwist (J) primeval story in Gen 2-4.

The last use of the toledot formula in the primeval story appears at 11:10. As you can see from the list above, it introduces vv. 11-26 which serve to connect Shem to Abraham. It serves as a transition from primeval time to historical time. Beginning with 11:27 which marks the opening of the cycle of stories associated with Abraham, we move into the time of the patriarchs and this will carry the story forward until the end of Genesis. Other appearances of the toledot formula will close out the Abraham cycle, begin and close the Jacob cycle, and introduce the Joseph story.

As far as the passage of 11:10-26 itself is concerned, there’s not much to say. It is a pure P genealogy with no variation to the rigid format. That said, there are some inconsistencies with other P genealogies and the biggest one concerns Arpachshad.

Back in 10:22 (another P passage), Arpachshad was listed as the third of Shem’s five sons: Elam, Asshur, Arpachshad, Lud, and Aram. In 11:10, it is recorded, “When Shem was 100 years old, he begot Arpachshad, two years after the flood.” The implication, of course, is that Arpachshad is the first-born, since genealogies are only concerned with the first-born son.

If that wasn’t enough, 5:32 states that Noah was 500 years old when he begot Shem. Gen 7:6 says that Noah was 600 years old when the flood came upon the earth. Simple arithmetic would give us the age of Shem as 100 when the flood began, yet 11:10 says that two years after the flood – a flood that lasted a year in P’s account – Shem was 100 years when he fathered Arpachshad.

This conundrum could tie a biblical literalist into knots trying to explain it. A non-literalist, however, could appeal to different traditions. But in this case, we are not dealing with the Yahwist (J) tradition on one hand and the Priestly (P) tradition on the other. All the passages cited come from P, so this passage actually demonstrates that the Priestly writer has several traditions before him that he is trying to preserve. We saw something similar in the Tower of Babel story where the J author was preserving separate traditions of how YHWH ended the tower-building project by either dispersing the population or confusing their language.

According to biblical scholars, in the P tradition that was taken up into the Table of Nations, Shem’s five sons represent five different nations: Elam (located in modern-day Iran), Asshur (Assyria), Arpachshad (Babylon), Lud (?), and Aram (Syria). But in the P tradition that appears in 11:10-26, Arpachshad is the name of a person who fathered Shelah.

The fact that P is combining and preserving pre-existing oral traditions that came to him demonstrates that the composition of the book of Genesis had a very complicated history. At the beginning of the process, you have a series of oral traditions that are handed down through the various tribes. At some point – probably around the time of David and Solomon – some of these traditions were written down by the Yahwist writer. Much later, around the time of the Babylonian exile, other traditions were preserved by the Priestly writer. Later still, the redactor (R) combined the J and P texts into Genesis as we have it today.

The inconsistencies and mismatches in the received text that are something of an embarrassment to biblical inerrantists allows the critical scholar to peer into the past to get a rough idea of how Genesis was put together. Or, as P would state it, “These are the generations (toledot) of Genesis when it was created.”